I live near the Atlantic Ocean, 80 kilometers north of the Cameroonian border with Equatorial Guinea. The Kengue/Kinke River is also in my town. Water has been controlled by SNEC (Societe Nationale des Eaux du Cameroun) since 1897. SNEC water is supplied by the Kengue River, and undergoes an elaborate filtering process that includes sand, bleach, aluminum sulfide, chlorine, and lime, which increases the pH level of the processed water.

(by Kathleen Reaugh, Batouri, East Province, Cameroon)

There has been no water since yesterday, and the electricity has been out for over four days. It's not that we're out of water, exactly—the Kadei River flows constantly past my town (in fact I think I can hear it taunting me now). But at seven kilometers it's a healthy trek for 15 liters of questionable water. That's probably all I could carry on my head for that distance, if it didn't all splash out. My water is always questionable though. It always comes straight from the Kadei, directly and unfiltered. An electric pump stores some of that water in a tower. But when the power is out, the water lasts for two days. So, on day two of the outage, I fill all the buckets I own (approximately 120 liters) and hope it will last as long as the outage. The Kadei's water is deceptively clear, masking amoebas and other parasites to which other Volunteers have fallen prey. For bathing and washing clothes, water straight from the Kadei is just fine.

(by Maryanne Pribila, Bogo, Extreme North Province, Cameroon)

My water comes from a well. The well is about a hundred meters from my house. It is a deep well, at least 30 feet. The water is always murky. During the hot season the water becomes sandy, because the well often dries up from the increased use of water. During the short rainy season, the water is an opaque color. I would never drink this water, but it works fine for washing.

(by Madhuri Kasat, Garey, Extreme North Province, Cameroon)

There are two year-round water sources: forages and wells. During the rainy season most people abandon these and go to the Mayo, or river, for their water. Usually, the Mayo flows like a river for a few hours after a heavy downpour, and then the waters retreat, leaving behind stagnant pools. This water is quickly contaminated. Nevertheless, many people prefer its taste to forage water and tell me that while I may get sick from river water, they possess an African immunity. During the dry season, from sunrise to sunset, the seven forages of Garey are adorned by queues of 50 to 100 buckets. Women and children place their buckets in line and then seat themselves beneath the shade of trees, sometimes waiting two to three hours for their bucket to arrive at the front of the line. By mid-dry season, pumping water requires considerable strength, but the forages have yet to dry out completely. The forages access a water table many feet beneath the Earth's surface. As a result, forage water tends to be hard—that is, concentrated with minerals and salts. But forage water is considered potable because forages are covered (as opposed to open, like wells or the river) by a concrete surface. Water is retrieved by pressing on a foot-pump. People are still advised to boil their water, as there have been outbreaks of epidemics such as cholera in the past years. But few people actually boil it.

Wells provide the third water source. Like river water, well water is softer and more palatable. Wells are generally left uncovered, however, unless it is a private well in someone's concession. Because of this, debris falls into the water. When the lines at the forages are too long to endure, women and children fetch water from the wells. During the rainy season (June–October), water lies in the riverbed at everyone's immediate disposal, but the dry season demands strategic planning or relentless patience. I know women who get up at 3 a.m. to avoid the lines at the forages.

(by Lea Loizos, Bati, West Providence, Cameroon)

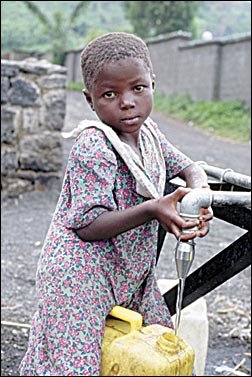

If you were to ask the people of Bati what their greatest problem is, many would tell you that it is the lack of clean water. There are many streams flowing throughout the village, but some of them dry up during the dry season, and none of them is very clean. Upstream, a woman may be washing clothes. Next to her, a few children are bathing. Downstream, a young girl comes to fill her bucket with water to take back to the house—unaware of the activities occurring upstream.

Luckily for me, there is an underground stream that was tapped near my house. The water flows out of a pipe and becomes an above ground stream. The source serves a large number of people in the community, as it is by far the cleanest water source in the village. During the dry season, the flow reduces to a trickle and people are forced to stand in line—sometimes for an hour or more—waiting for those ahead of them to fill their buckets. Fortunately, people often let me cut to the front of the line out of respect; I guess they know I'm not used to fetching water every day. In fact, people still giggle as they see the American woman walking down the road with a bucket on her head. During the remainder of the year—the rainy season—I catch the rainwater that falls off my roof by placing numerous buckets and pots outside. That's usually enough to hold me until the next rain.

No comments:

Post a Comment