Cameroon: Little to Quench the Nation’s Thirst

"If you knew how many plans and resolutions there have been about our country’s water problems, you would be hard put to understand why (people are) still without potable water," Daniel Manguelle of Catholic Relief Services, a non-governmental organisation, told IPS.

"But there’s nothing inherent about our country that has forced us to have these problems."

According to Manguelle, plans to improve Cameroon’s water system fail because of delays in execution – or because of the corruption which plagues large water deals. In the case of ‘Yaounde Horizon 2000’, a multi-million-dollar project to provide water to the Cameroonian capital and surrounding areas by 2020, several officials were accused of demanding payoffs.

Only 60 percent of the project was ultimately completed, and the contracting company, Collavino, quit in disgust.

According to a 2003 report by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), only 44 percent of Cameroon’s 15.8 million strong population has access to clean water. This translates into seven out of 10 households in the country’s main cities, compared to one in four households in rural areas.

The lack of clean water has, on occasion, had disastrous consequences. Between January and March of this year, an outbreak of cholera claimed 26 lives in the economic hub of Douala. In 2000, thirty people died in the east of the country as a result of diarrhea – another disease related to the consumption of dirty water.

"We’re aware of the dangers our people incur," the Secretary-General of the Ministry of Mines, Water and Energy, Fritz Nassako, told IPS. "A project dealing with water access is in the final phases of completion to remedy water supply problems nationwide," he added.

The first phase of the project (1998-2000) focused on assessing what water-related infrastructure was already in place. "The study will allow a better understanding of the best ways to supply potable water to urban areas and their vicinities," says Nassako.

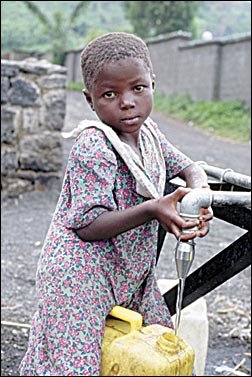

According to Joseph Ngoua of the Water Office, "The minister envisages the provision of either a well or a borehole equipped with a hand-powered pump for every 300 to 500 people, with an average consumption of 25 liters a day per person." It is hoped that the project will be financed by funds that are freed by partial debt forgiveness for Cameroon.

However, some fear the government’s plan could be derailed by a failure to address the sanitation problems that are already compromising existent wells. "Douala hardly has a sewer or drainage system," says Jules Kamgang, an urban planner in Yaounde.

Adds Max Antoine Grolleron, head of the Doctors Without Borders mission in Cameroon, "Several of the town’s 8,000 wells are not protected and are located near latrines, which end up contaminating them."

In a bid to address these concerns, government began a campaign in March to sanitise the city’s wells by putting chlorine in them. About 4,850 wells in Douala have been treated to date; 3,150 remain. Health authorities are also urging people to keep latrines and garbage away from wells.

‘Douala 2005’, a programme financed by the French Development Agency at a cost of about 19 million dollars, is another project in the pipeline. It aims to renovate the city’s entire water network – and finance the construction of up to ten pumping stations.

In the meantime, some look to privatization of the Societe Nationale des Eaux du Cameroon (the Cameroonian National Water Company, SNEC) as providing a possible way out of the morass.

"I hope that privatization of the SNEC will contribute to improving supply, and to renovating and maintaining infrastructure," Catherine Mballa, a member of the non- governmental organization ‘Women, Health, and Development’, told IPS. (It is estimated that only 15 percent of households are connected to SNEC.)

But according to Christophe Ebong, a lecturer at the University of Yaounde I, this will only make matters worse. "Western firms who buy companies want to make a profit. They are not in the business of investing. In the case of the SNEC, it makes me laugh when I hear people putting their faith in privatization."

Although government has started the process of privatizing SNEC, Cameroonians have yet to derive any benefit from it. The company has been forced to raise the price of a connection to the national water system from 472 dollars to 943 dollars in certain cases. SNEC has also increased the price of water from 26 to 51 cents per cubic metre. This amount is completely beyond the reach of many Cameroonians – particularly those in rural areas. According to the UNDP, 75 percent of the rural population lives below the poverty line of a dollar a day.

No comments:

Post a Comment